Gary, Indiana, is a city that is no stranger to loss. Its once thriving steel industry now stands as only a shadow of its former self, and with its decline came a still-rising tide of blight. The city’s once glittering Broadway is now lined with boarded up storefronts and crumbling buildings. Now, as Gary struggles to reinvent itself, it faces yet another painful loss: its central library.

The library’s fate is not a new idea to the nearly 80,000 people who still call Gary home. Last March, the Gary Public Library’s Board of Trustees voted 4-3 to shutter the 48-year-old main library on 5th Avenue as well as its Tolleston branch location. Board president Tony Walker told the Chicago Sun-Times that the closing was necessary to prevent the city’s remaining four branch libraries from suffering the same fate. The idea was that the board could only stop the library’s budget bleeding by cutting off the head.

A patron takes a look at the Gary Library's collection of video media on its last day of operation.

Gary’s city coffers, like most metropolitan areas, are filled every year by a number of revenue streams including things like fees for parking permits, fines for petty offenses, and sales taxes. However, these only provide fractions compared to the biggest single source of municipal revenue: property taxes. In 2009, Indiana voters passed an amendment to their state’s constitution capping property tax rates at 1/2/3 percent (residential, commercial, and industrial rates respectively) of assessed value. While this amendment fixed taxes at a predictable rate for citizens and business owners, for Gary’s checkbook, it was a big problem for one simple reason: abandoned buildings (of which there is no shortage in Gary) do not pay a cent of property tax. All it takes is a short walk from the South Shore line train station towards Gary's downtown to see the stunning level of urban decay afflicting Gary; some buildings look like they would blend in better in Sarajevo circa 1992, burned out and full of holes. The city’s post office, train station, main hotel, and historic Methodist church all lie abandoned, disused and in real estate limbo; too expensive to either demolish and rebuild or renovate and reuse.

Gary’s City Methodist Church has been abandoned since the early 1980s. Plans for redevelopment have been made and shelved time and again, but the church stubbornly remains standing, even after being set partially ablaze in the Great Gary Arson of 1997.

While nearby cities like Hammond and South Bend have made do with the tax cap, they also have the advantage of far lower vacancy rates than Gary – and by the same token, more taxpaying property owners. Without the ability to independently raise tax rates to make the difference in funding up, Gary’s civic leaders applied every year, starting in 2009, for a special exemption to the cap amendment in order to keep the city’s basic services – fire and police departments, streetlights and the like – away from the axe. Further exemptions were given in 2010 and 2011, allowing the city to charge up to an additional 0.68 of a percent on businesses and industrial properties including the still impressive US Steel mill at the edge of Lake Michigan.

However, when the state’s Distressed Unit Appeals Board (DUAB) granted its final yearlong exemption last April, it did so with the express condition that this was the last time – next year, Gary would have to make do with the standard 1/2/3 percent tax rates for the state, come hell or high water. For Gary, this meant that keeping the streets lit and police and fire departments intact would mean looking at other places for cuts. And with projected revenues now falling even further away from forecasts, the option of closing the main library became truly viable, a means by which the city could try to stem the tide of the recession.

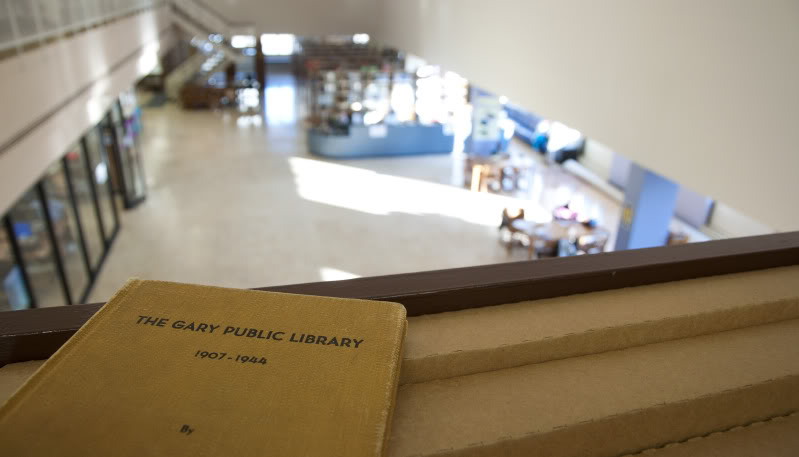

Fast forward now to the last week of 2011, and that reality is all too certain. Signs proclaiming this, December 30, to be the final day of the Gary Library are posted all over the entrances to the building as I walk in. The librarians behind the desk go about their work as if it were any normal day, but have a sort of forlornness and resignation in their movements. One of them comes out from a room filled with towers of books waiting to be sorted, and takes me upstairs, keys clanking through the deserted hallway, to the pride of the Gary Public Library: the Indiana Room.

This upstairs sanctuary is home to a unique repository of materials, some dating back past the founding of Gary to the genesis of Indiana itself. The smell up here is different than the rest of the library; mustier and palpably old, the scent of aging, hand-bound books and antique parchment maps. Obscure titles like: “The Life of Elbert H. Gary – The Story of Steel” and “Lake and Calumet Region of Indiana – Historical 1917-1918” share shelf space with old blueprints, phone books and church directories.

Up here, Rufus Purnell spends a little time with the archives before the library closes down. Purnell grew up in Gary, and this library, which has been open almost as long as Purnell has been alive, was a fixture in his youth as well as his adult life. “They even asked me to join the board (of trustees) three times!” he exclaims. His enthusiasm for Gary’s library is apparent, but also in turn his sadness at its closing.

“I’m just afraid that someday, libraries…they’re going to be a thing of the past. You’ll have to be a rich city to have a library,” he tells me, looking out over the reading room speckled with patrons. “We are a community,” he says, “and we really need a library. Everybody don’t [sic] have internet, and sometimes people just need a place to go.”

Purnell then takes another look at a shelf, examining it for a moment before finding something that catches his eye. “Well, hell, it’s even the right year!” he exclaims, taking a weathered high school yearbook off the shelf. The year on the cover is 1971, and Purnell flips the pages until, sure enough, he finds a sharp-looking, afro-sporting photo of himself in his younger years. He chuckles and tells me that thankfully, these archives will be saved – for better or worse.

Rufus Purnell looks through the Indiana Room's collection of high school yearbooks. His photo appears in the book in the foreground, on the top row of the left page, near the fold.

Downstairs, librarian Charles Matthews flips a book open, hunts around for a bar code, and scans it back into the library’s system with a *beep* from his computer. Matthews grew up not far from here, in Merrillville, and was a library patron from early on. “Oh yeah, I remember when they first got VHS tapes back in the day!” he tells me excitedly.

Williams has been a librarian here for three years now, but tomorrow he might not have his job anymore. Though the library’s management is doing what it can to preserve the jobs at the Central branch by moving them elsewhere, he tells me that there’s still a lot of uncertainty over whether or not the inevitable layoffs will claim his job. That’s not all the uncertainty in the air, either, as neither Williams nor the other librarians yet know the plan for what will be done with all the library's books come tomorrow. Though the Indiana Room’s priceless collection is certain to be saved, the rest of the library’s sizeable media collection will have to be moved and stored somewhere or sold off if ‘disposal’ is to be avoided. Williams’ best guess is that they’ll be stored at the other branch libraries in Gary’s system, but he concedes that he knows of no timetable for when this move could happen. He looks out over the reading room again, flips open another book, and tells me: “I hate to see it happen like this…I’d love to see it reopen as an even better library.”

Charles Matthews checks a book into the Gary Public Library’s system on the last day of the Central branch’s operation.

The Central branch's reading room begins to empty out as the end of the library's last day approaches.

The sun starts to stretch through the big plate glass windows in the reading room, heralding the final stretch in the Central Library’s last day. Soon, the real task begins: clearing the building in order to manifest the Board of Trustees’ final vision for the Central Library, a rebirth as the South Shore Museum & Cultural Center. This proposal would see the building undergo a $2 million conversion into a museum that would house exhibits on the history of the city, a computer lab, and a state-of-the-art theater. The building’s redesign would be done locally, by a branch of the architectural firm of Forms + Funktion. The idea is that the cultural center will preserve the history of the city – including things like the Indiana Room – but will cost less to operate than the library, thus leading to long-term cost savings.

However, many Gary residents question the logic behind spending such a multi-million dollar amount on a renovation when even the consultants hired by the Board agree that the building is structurally sound and in no need of repair. Gary’s citizens aren’t being silent, either; as of this writing, petitions are circulating in Gary that not only oppose the closing of the library – some even call for the recall of the board members who voted to close the library.

Whatever happens to the Gary Central Library, one thing remains certain: the book on this fragile part of the city’s fabric is anything but closed.